Nebraska REINS Act: A good-government way to provide oversight of major regulations

Regulatory policy, writes William Ruger and Jason Sorens for Cato Institute’s Freedom in the 50 States project, “is the most important policy variable in terms of explaining economic growth in the states.”1

How can something so important to a state’s economic growth be so easy to overlook? One reason could be that regulatory burdens aren’t easily quantified, like tax burdens. But another reason could be that the bureaucratic process of making regulations is also overlooked.

What are regulations?

Regulations are the “rules of the game” for doing business within the state. At their best they can provide a clear picture of legal boundaries. They can remove uncertainties, questions about rights, and inefficiencies so individuals and business enterprises can operate and compete in the state with confidence.

But regulations can also pile up on top of each other, outlive their original purpose, produce negative unintended results, seem arbitrary, persist even when they do more harm than good, and help only regulators or special interests.

What is red tape?

At some point, regulations create more problems than they solve. When rulemaking goes beyond setting the right boundaries for individuals and business, people call it red tape.2 Red tape is an officious, bureaucratic tangle that takes people’s time and energy away from doing something productive.

The worse red tape gets, the more it causes would-be startup ventures, private enterprisers, and even outside corporations mulling moves and expansions to think, “Why bother? It’s not worth the hassle.”

How red tape slows a state’s economic growth

When people and businesses produce goods, services, and innovations, this creates more economic activity, more sales, more job growth, and ultimately more wealth. It’s a beneficial growth spiral that feeds off itself.

Red tape, however, causes people and businesses to spend time and effort satisfying the requirements of government bureaucrats. That means they’re hindered from producing as many new goods, services, and innovations as they otherwise could, zeroing out that much economic potential, year after year. Adding to those hindrances every year zeroes out even more potential economic growth.3

This is why regulatory policy is so important, even if its effects cannot be quantified like tax policies’ effects can. Letting red tape grow like weeds chokes off potential economic expansion. (See Appendix A for a discussion of the cumulative effects of regulations on the economy.)

Preventing red tape from growing unchecked, however, protects the state’s economic vibrancy and potential for growth.

Regulation and the Separation-of-Powers Problem

What makes it hard to check the growth of red tape is how regulations begin. Regulations behave like laws. They are rules backed and enforced by the power of the state.

Their main practical difference from laws is in how they originate, but that is the key. Laws are created in the legislative branch of the government, made by legislators, who are elected representatives of the people tasked with making laws.4 Regulations are created in the executive branch of the government, made by agency bureaucrats who aren’t elected and who don’t answer directly to the voters for their decisions.

Regulations are rules with the force of law, but they are not made by legislators. How is that? Because legislators have delegated a limited authority to the agencies to make rules that help implement their laws. This makes sense in that legislators have limited time and cannot be subject-matter experts in every endeavor. They set the policy and leave it to the executive branch agencies to put it into execution.5

The incentives in rulemaking can lead to red tape

Most rules have minor impacts and are the nuts and bolts of implementing the Legislature’s will. Some rules, however, have major impacts that may go beyond what the Legislature would have wanted. Either way, both kinds of rules have the same adoption process, and it’s a process that’s much easier than passing a bill into law.

In short, regulations behave like laws, but they are easier to make, require less deliberation, and get made by people who aren’t directly accountable to voters.

Nebraska’s Administrative Procedure Act (APA) gives the process for an agency adopting a rule. There are several procedural steps that must be followed for a proposed rule, but adoption is the expected outcome.6 While one step is to notify the Executive Board of the Legislative Council,7 oversight on proposed rules comes from the executive branch: the Attorney General can determine a rule lacks statutory authority or constitutionality,8 and the Governor may decide not to approve the rule.9 The APA also allows judicial review of a regulation in a contested case.10

What can the Nebraska Legislature do about problematic agency rules?

Under current Nebraska law, the only entity who can stop a proposed agency rule or regulation from taking effect is the Governor. The two conditions necessary for a rule or regulation to take effect are that it has been approved by the Governor and filed with the Secretary of State.11

But what about the Legislature? Executive branch agencies only have rulemaking power as delegated to them by the Legislature. What if a member of the Legislature has good reason to object to the rule? What process does Nebraska have to address such a basic concern?

Here is the procedure given in the Administrative Procedure Act, in brief:

• A member of the Legislature determines the proposed rule: exceeds its statutory authority, is unconstitutional, doesn’t align with legislative intent, creates an undue burden on the public, has become moot by changing circumstances, or overlaps, duplicates, or even conflicts with existing federal, state, or local laws, rules, or ordinances

• The member gives a detailed complaint to the chairperson of the Executive Board of the Legislative Council

• The complaint is forwarded to the chairperson of the particular standing committee of the Legislature that the issue affects and, when possible, also the primary bill sponsor of the legislation that authorized the rule

• If they deem the complaint is merited, they request a written response from the agency responsible for the rule

• The agency’s response will be a public record and should come within 60 days, including: a description of the rule; an explanation of how the rule fits its statutory authority, is constitutional, aligns with legislative intent, or is not an undue burden; or barring that, why it is necessary; and an explanation of how the agency took public comment into consideration in rulemaking

After all that, however? “Nothing in this section shall be construed to prohibit the adoption or promulgation of the rule or regulation in accordance with other provisions of the Administrative Procedure Act.”12

The APA does have a process for a legislator to file a complaint against an adopted regulation for several reasons: if it exceeds its statutory authority, goes beyond legislative intent, is unconstitutional, has costs significantly greater than its benefits, is outdated, or is duplicative or contradictory of other laws or rules. The end result of this process, however, is that the agency provides written explanation to the Legislature as a matter of public record.13

Lack of legislative oversight makes overregulation and red tape more likely. Unelected bureaucrats have greater range to craft regulations in ways that make their job easier, without regard to original legislative intent.

A 2015 performance audit from the Legislative Audit Office found several problems with Nebraska’s rulemaking process and with how agencies interpreted it. Notably, the audit found instances where agencies even skipped giving public notices or hearings.14

Again, regulations impose costs on people and businesses and slow a state’s economy. Sometimes this tradeoff is worth the clarity and stability they bring to their respective policy areas. Other times, however, regulations can impose large costs. When it comes to such major regulations, it doesn’t serve the principles of good government for them to be imposed unchecked by regulatory bureaucrats. They aren’t the ones answerable to the voters.

Legislators should be able to double-check a major regulation to make sure it’s the right choice for the state—that its expected costs are worth it. Providing this good-government double-check is the goal of legislation known as the REINS Act.

Nebraska’s Regulatory Climate

Before describing the REINS Act, however, it would be useful to take stock of Nebraska’s regulatory climate. In so doing, this paper notes that Nebraska policymakers are currently engaged in regulatory reform. It is a process this paper wishes to encourage and supplement, so that the snapshot provided here will be a contrasting “before” picture.

Recent examinations of Nebraska’s regulatory climate have found it to be a mixed bag concerning restrictions against individuals and business. For example, the 2017 Nebraska Administrative Code contains 100,627 regulatory restrictions. It is 7.5 million words long, which would take a person over 10 weeks to read. That’s according to a July 2017 report from the Mercatus Center at George Mason University.15

The estimable cost of state regulations on Nebraska’s private sector for a single year was $473.8 million in 2016. That estimate is from economists at the Beacon Hill Institute, but the actual cost is much, much larger. Given the difficulty in determining the opportunity costs of state regulations on the private sector (see Appendix A), the economists noted that “after reviewing the Nebraska Administrative Code, we believe our figure represents a fraction of the total cost to the private sector” (emphasis added).16

The Cato Institute’s Freedom in the 50 States project ranks Nebraska second in the nation for regulatory freedom. That measure includes such things as land use, health insurance, labor market, occupational regulation, lawsuits, and other areas of regulation.17

The 50-State Small Business Regulation Index of 2015 ranked Nebraska twelfth overall. The state had high marks for unemployment insurance, short-term disability insurance, family leave, and right-to-work regulations. Nebraska compared unfavorably in terms of start-up and filing costs, minimum wage laws, and telecommunications regulations, and it got especially poor marks in occupational licensing and regulatory flexibility.18

Nebraska’s state regulatory costs take on a greater importance in light of how Nebraska’s economy is particularly affected by federal regulations. Nebraska’s unique blend of industries leaves it open to a greater hit from federal regulations than most other states. A Mercatus study indexing federal regulations to specific state industries found that “the impact of federal regulations on Nebraska’s private sector was 24 percent greater than the impact of federal regulations on the nation overall.” In that study, Nebraska ranked as the fifth most affected state by federal regulations.19

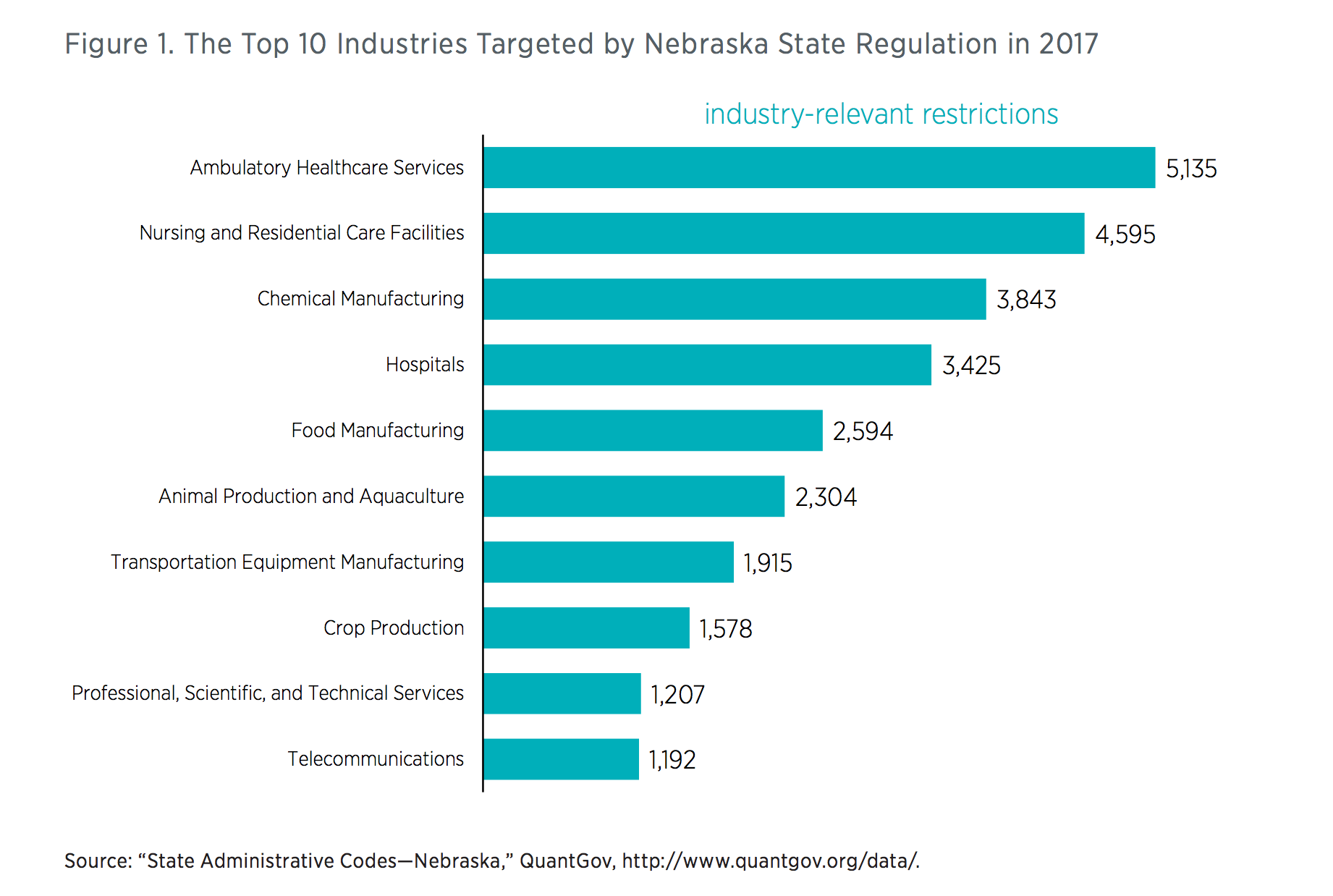

Top 10 Industries Targeted by Nebraska State Regulations in 2017

Recent interest in reform

Being more hamstrung by federal regulations than most, Nebraska policymakers must be extra careful not to make things worse for the private sector with the state regulatory climate. Nebraska policymakers will need an ongoing commitment—and the right policies—to help guard against growing a costly, restrictive regulatory regime.

Nebraska’s policymakers appear willing to tackle this problem. For example, one of the three regulatory cost burdens calculated by BHI was “Fees, licenses and permits paid to the state.”20 Nebraska ranked 44th in “Occupational Licensing and Certification” in the 50-State Small Business Regulation Index.21 In 2018, the Nebraska Legislature passed and Gov. Pete Ricketts signed the Occupational Board Reform Act, a landmark occupational license reform. Among other things, it included protecting the right to pursue a lawful occupation, adopting the standard of least restrictive regulation necessary, and periodic review of occupational licensing.22

On July 6, 2017, Ricketts issued an executive order to review state regulation. Among other things, Ricketts issued a temporary suspension of rulemaking and ordered state agencies to “review all existing and pending regulations” and issue a report to his office of the findings. Each regulation was to be evaluated on the following criteria:

- If it was “essential to the health, safety, or welfare of Nebraskans”

- Whether its costs outweighed its benefits (based on “specific data and reasoning”)

- If there was a process to measure its effectiveness

- If a less restrictive alternative to the regulation was considered

- If it was based on a state statutory requirement or federal mandate23

Ricketts’ order called for this report to be delivered to his office by November 15, 2017, but it was unavailable as of this writing.

The Legislature and governor are taking positive steps toward regulatory reform. A state REINS Act would be an important tool in this effort. (Appendix B includes several other regulatory reforms to consider as well.)

A REINS Act for Nebraska

A REINS Act would restore legislators’ oversight to proposed major regulations. In other words, REINS would restore the lawmaking authority that was unduly delegated to executive agencies.

The focus of REINS, which stands for Regulations from the Executive In Need of Scrutiny, is only on rules that would have a significant economic impact on the state. Under REINS, a major regulation either receives scrutiny from the Legislature or simply doesn’t take effect.

In 2010, Florida enacted a major regulatory reform law with REINS-like provisions.24 The REINS idea became known as such when the U.S. House passed a federal REINS bill in 2011 (and in subsequent years: 2013, 2015, and 2017).25 In 2017, Wisconsin enacted a state REINS law.26 REINS-inspired provisions passed both chambers in the North Carolina General Assembly in 2018, but were not enacted owing to unresolved differences in other portions of the bill.27 Also in 2018, Tennessee legislators opened debate over a REINS Act.28

What REINS does

Under REINS, economic cost estimates must be prepared for proposed rules. Each regulation would receive economic analysis to quantify the dollar amount of economic costs it is expected to have on the state’s economy. If that cost estimate exceeds a certain threshold amount set by the Legislature in the REINS text, the rule would be considered a major regulation. For example, in the Florida law, the threshold is an adverse impact or direct or indirect increase of regulatory costs on small business by $200,000 in a year (i.e., $1 million in five years).

Once a major regulation has undergone the Nebraska rulemaking procedure and been filed with the Secretary of State, it would be submitted to the Government, Military and Veterans Affairs Committee for approval or disapproval. That is the committee responsible for processing legislation involving administrative rules and regulations. The committee will then either introduce a bill to the Legislature to authorize the regulation or request that the agency modify the rule to lower its costs—or withdraw the rule altogether.

Importantly, the Legislature is not obligated under REINS to vote to affirm a major regulation. The regulation must be compelling enough to merit it. Unless the Legislature passes a bill affirming the regulation, however, it cannot go into effect. It will stay on the books but not take effect.

What REINS doesn’t do

REINS is narrowly focused on restoring legislative oversight to major regulations. It doesn’t affect minor regulations or regulations with projected economic impacts below the threshold level set by the Legislature. It won’t hamstring normal agency rulemaking. In the first four years of the Florida law, only 36 of the 8,535 rules needed legislative review.29

Emergency regulations also don’t fall under REINS, nor do regulations required by federal law.

REINS is not a tool for reducing existing regulations. It also doesn’t get rid of other oversight provisions already in the statutes to check regulations, minor or major.

What REINS is, then, is a good-government check against adding major regulations without making sure they conform to the Legislature’s intent. It fixes the separation-of-powers problem of unelected bureaucrats, instead of legislators, making laws with significant impact.

The key to this reform is this: it doesn’t obligate the Legislature to hold the affirming vote needed for a major regulation to take effect.

With and without a REINS process

For example, from 2012 to 2014 the Florida Legislature declined to consider a major rule from the state Department of Financial Services (DFS) that would have changed reimbursement rates for workers’ compensation.30 It would have been the first such change since 2008, and it would have significantly increased costs on Florida businesses (an estimated $272 million over five years).31 The Florida legislature did not pass a bill ratifying DFS changing workers’ compensation reimbursement rates until 2016.32

That was not the only time the law required the Florida Legislature to engage in an important debate over high-cost regulations. After a dozen nursing home residents in Hollywood, Florida, died in 2017 when Hurricane Irma left them without power in sweltering heat without air conditioning, Gov. Rick Scott favored new rules that would require nursing homes and assisted living facilities to have backup generators and three days’ worth of fuel on site. The rules would cost nursing homes an estimated $125 million33 and assisted living facilities an estimated $244 million34 over five years.

The debate over the ratification bills (one for nursing homes and one for assisted living facilities) was contentious, the final outcome was not certain, and alternative proposals were also debated.35 Eventually, both ideas were ratified, and since then several facilities have been given extensions in meeting the mandate.36

A few years before approving Wisconsin’s REINS Act, Wisconsin lawmakers were surprised at the staggering cost of a 2010 state Department of Natural Resources rule to limit phosphorus pollution in lakes and waterways. The rule exceeded the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s requirements. After the rule took effect and was being implemented, however, local communities and businesses sounded the alarm. The legislature sought a detailed economic analysis of it, discovering that the bill would have an estimated cost of up to $7 billion over the next 20 years.37

North Carolina lawmakers debating REINS-like provisions in 2017 learned from legislative staff that the bill’s five-year cost threshold of $10 million would have affected only a small number of rules over the past six years. For example, one rule by the state Industrial Commission made a significant structural change in workers’ compensation billing and payments. It required and standardized electronic medical billing and payments in response to legislation passed in 2012.38 Another rule was from the Department of Health and Human Services, implementing state legislation from 2015 that forbid tanning salons from letting anyone under the age of 18 use their equipment.39

Previously, the cutoff age was 13, but there had been an exception that allowed younger children to use tanning equipment if they had a medical prescription specifying it for treatment of a specified medical condition for a limited amount of time.40

What other things REINS can bring about

These two aspects of REINS—the focus only on major rules and the Legislature not being required to take an affirming vote—can produce several beneficial side effects.

For example, it can prompt legislators to be more careful in drafting laws. When agencies try to flesh out unclear or overly broad mandates from the Legislature, they’re more likely to create major regulations—which would require the Legislature’s vote anyway.

Also, it can compel agencies to be more careful in crafting rules. Their interest will be to stay below the cost threshold for major rules, so as not to undergo the uncertainty of legislative review.

When an agency needs to produce a rule that cannot stay below the cost threshold, they’ll want to work together with the Legislature to make sure the resulting major rule is acceptable to the Legislature. This aspect should open communications between agency staff and the Legislature and make the process more transparent.

The Florida law resulted in the agencies’ lawyers and legislative bill drafting experts producing a model template for a general bill to affirm a major regulation.41 The rulemaking subcommittee, with guidance from the agencies, produced recommendations on how to identify and quantify a rule’s costs and affected parties. Five years after the law’s enactment, a review of the process by the Florida Bar Journal found that the process had become “routine” and that “the legislature has moved with dispatch” to decide whether to affirm the major rule or not.42

This emerging cooperation would be a good-government outcome by itself. Since the agencies are tasked with implementing the will of the Legislature in their respective scope of operations, more communication with the Legislature can only help bring that about.

Conclusion

By putting a check against major regulations, prompting agencies to be more mindful of the economic impact of proposed rules, and inducing legislators to take greater care not to over-task the agencies into needing to create major regulations, REINS would slow the expanse of red tape in Nebraska. As a result, Nebraska would benefit from a stronger climate for economic growth.

It would be an especially timely addition after the executive and legislative reviews of all agency regulations and occupational licenses.

As Nebraska’s leaders continue to streamline the state’s regulatory climate, having a policy to require a legislative double-check before imposing a major regulation on the state’s economy would work to keep the regulatory system streamlined. Research shows that would enable the private sector to expand faster and Nebraska’s economy to grow stronger than otherwise, compounding greater growth year over year.

About the Author

JON SANDERS is Director of Regulatory Studies at the John Locke Foundation and an adjunct instructor of economics at the University of Mount Olive. He focuses his analysis on state rulemaking, electricity policy, occupational licensing, hydraulic fracturing, the minimum wage, poverty and opportunity, film and other incentives programs, certificates of need, and cronyism.

Appendix A: Cumulative cost of regulations

The idea that red tape and regulations can not only harm economic growth, but have compounding harm to economic growth, is not easy to understand at first. No doubt it is because the costs are unseen. They represent what economists call “deadweight loss,” lost gains from trade because of market inefficiencies that prevent some trades from happening.

They’re not costs in the sense of paying income taxes and seeing the dollar amount withheld by the government. They are costs in the sense of absence of economic gains that would otherwise be taking place but for the stifling effect of red tape.

Still, these costs of regulation are a consistent finding across the great bulk of economic studies of regulations’ effects. In their landmark paper on lost economic productivity from federal regulatory activity, economists John W. Dawson and John J. Seater surveyed many new studies of the macroeconomic effects of regulation, finding that “[a]lmost all these studies conclude that regulation has deleterious effects on economic activity.”43

Year in and year out, as the economy fails to progress as far as it otherwise could without the red tape, the costs grow deeper. Worse, continuing to add red tape compiles new costs upon costs already ongoing.

Estimating the costs of red tape over time is not easy. Most economic studies of the issue will focus on the effects of federal regulation. Drilling down to the state level and disaggregating state regulations’ effects from federal regulations’ effects and other factors on the state is a very heavy lift.

That said, the same compounding negative effects produced by red tape at the state level can be expected to mirror those of red tape at the federal level.

Two recent economic studies attempted to estimate the compounding effects of federal regulations over time. Both studies picked a different starting point and estimated how much the economy could have grown had the level of regulation remained constant and not continued to grow. Both studies found the economy significantly smaller than it otherwise could have been, leaving people in general less well off than they could have been.

In one study, economists Bentley Coffey, Patrick McLaughlin, and Pietro Peretto estimated the effects of new federal regulations added since 1980. They found the U.S. economy could be 25 percent larger (about $4 trillion larger) than it actually was—a loss of about $13,000 per person.44

In their study, Dawson and Seater used 1949 as their starting point for estimating the effects of new federal regulations added since that time. They estimated the U.S. economy to be only about one-fourth the size it actually could be—a loss of about $129,300 per person (or $277,100 per family).45 They also found that accumulating federal regulations slowed the nation’s economic growth by 2 percent a year on average.46

Appendix B: Other regulatory reforms to consider

This paper notes efforts by the Nebraska Legislature and the governor to streamline the state’s regulatory environment. What follows are proposals of other regulatory reforms to build from and help in this effort.

Sunset provisions with periodic review

This is the one rules review process found by researchers at the Mercatus Center to have “robustly statistically significant” evidence of reducing a state’s regulatory burden, with positive—and “economically significant”—results.47 North Carolina passed sunset provisions with periodic review in 2013, and by 2018 it had removed about one out of every eight rules under review.48

The Occupational Board Reform Act of 2018 includes periodic review for occupational regulations; this reform would extend periodic review to other areas of regulation as well.49

Accountability to stated objectives and outcome measures

With periodic review, a rule under review should be judged according to its foundational purpose, not whether it created an unintended benefit for a particular group who then has a lobbying interest in retaining it. Nebraska’s APA requires agencies to accompany a proposed rule with a concise explanatory statement giving the rationale behind the rule.50

This reform would build upon that to give the objectives and expected outcomes of the regulation if it works as intended. A rule that failed to produce its intended effects or meet its objectives would not be allowed to pass review, so it would not go on creating unintended problems for the state.51

Small business regulatory flexibility

Nebraska is one of only a few states to lack regulatory flexibility for small businesses. Regulations’ impact on small businesses are disproportionately greater than they are on big businesses with personnel dedicated to regulatory compliance. For that reason, over two-thirds of states and the federal government have the ability to adjust regulatory burdens (such as compliance and reporting requirements) as they apply to small businesses.52

In 2018, 99.1 percent of businesses in Nebraska were small businesses.53

No-more-stringent laws

Where state and federal regulation overlap, no-more-stringent laws forbid regulatory agencies from imposing a stricter, costlier red-tape environment on small businesses and local industries than the federal government already does (such as happened in Wisconsin). The idea is similar to the “least restrictive regulation” standard in the Occupational Board Reform Act of 201854 and the “less restrictive alternative” portion of the review in the governor’s regulatory reform executive order.55

No-more-stringent laws wouldn’t, however, prevent the Legislature from voting to enact stricter standards.

The underlying issue is good government with accountability to voters. Making a major, structural change to the state’s laws is the role of elected representatives in the Legislature, not of unelected bureaucrats.

Endnotes

1. William Ruger and Jason Sorens, “Freedom in the 50 States: An Index of Personal and Economic Freedom,” Fifth Edition, 2017- 2018, Cato Institute, p. 61, https://www.freedominthe50states.org/ print.

2. See Jon Sanders, “Good ‘red tape’ vs. regulatory rigmarole,” Research Update, John Locke Foundation, February 13, 2013, https://www. johnlocke.org/update/good-red-tape-vs-regulatory-rigmarole.

3. See John W. Dawson and John J. Seater, “Federal Regulation and Aggregate Economic Growth,” Journal of Economic Growth, Springer, vol. 18(2), June 2013, pp. 137–177; Working Paper version viewable at https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers. cfm?abstract_id=2223315.

4. Constitution of the State of Nebraska, Articles II-1 and III-1, viewable at https://nebraskalegislature.gov/FloorDocs/Current/PDF/ Constitution/constitution.pdf.

5. “It is a well-established principle that the Legislature may delegate to an administrative agency the power to make rules and regulations to implement the policy of a statute.” Yant vs City of Grand Island, 784 N.W.2d 101 (2010), 279 Neb. 935, No. S-09-664, viewable at https://caselaw.findlaw.com/ne-supreme-court/1607610.html.

6. Nebraska Revised Statute 84-901.01, https://nebraskalegislature. gov/laws/statutes.php?statute=84-901.01.

7. Nebraska Revised Statute 84-907.06, https://nebraskalegislature. gov/laws/statutes.php?statute=84-907.06.

8. Nebraska Revised Statute 84-905.01, https://nebraskalegislature. gov/laws/statutes.php?statute=84-905.01.

9. Nebraska Revised Statute 84-908, https://nebraskalegislature.gov/ laws/statutes.php?statute=84-908.

10. Nebraska Revised Statute 84-917, https://nebraskalegislature.gov/ laws/statutes.php?statute=84-917.

11. Nebraska Revised Statute 84-908.

12. Nebraska Revised Statute 84-907.10, https://nebraskalegislature. gov/laws/statutes.php?statute=84-907.10.

13. Nebraska Revised Statute 84-907.10.

14. “Nebraska Administrative Procedure Act: Review of Selected Agencies and Best Practices,” Performance Audit Committee, Nebraska Legislature, September 3, 2015, viewable at https:// bloximages.chicago2.vip.townnews.com/journalstar.com/content/ tncms/assets/v3/editorial/4/d5/4d5c181c-107f-5aef-808f- 56f5cbc5069d/55e8a91c85a5e.pdf.pdf.

15. James Broughel and Daniel Francis, “A Snapshot of Nebraska Regulation in 2017,” Policy Brief, Mercatus Center, George Mason University, July 2017, https://www.mercatus.org/publications/ snapshot-nebraska-regulation-2017.

16. Paul Bachman and David Tuerck, “The Cost of Regulation in the State of Nebraska,” The Beacon Hill Institute, April 2017, https:// www.platteinstitute.org/library/docLib/The-Cost-of-Regulation-in-the-State-of-Nebraska.pdf.

17. Ruger and Sorens, “Freedom in the 50 States,” Nebraska entry, viewable at https://www.freedominthe50states.org/occupational/nebraska.

18. Wayne Winegarden, “50-State Small Business Regulation Index,” Pacific Research Institute, July 2015, https://www.pacificresearch. org/the-50-state-small-business-regulation-index.

19. “Frase 2017 State Brief: Nebraska” from “The Impact of Federal Regulation on the 50 States,” QuantGov platform, Mercatus Center, George Washington University, http://resources.quantgov.org/ state_briefs/nebraska.pdf.

20. Bachman and Tuerck, “The Cost of Regulation in the State of Nebraska.”

21. Winegarden, “50-State Small Business Regulation Index.”

22. LB 299, https://nebraskalegislature.gov/bills/view_bill. php?DocumentID=31200. For discussion of its import, see, e.g., Editorial Board, “A Model for Licensing Reform,” The Wall Street Journal, April 3, 2018, https://www.wsj.com/articles/a-model-for-licensing-reform-1522795235, and Nick Sibilla, “Nebraska Governor Signs Landmark Reform for Occupational Licensing,” Institute for Justice, April 23, 2018, https://ij.org/press-release/ nebraska-governor-signs-landmark-reform-occupational-licensing.

23. Gov. Pete Ricketts, Executive Order No. 17-04, “Regulatory Reform,” State of Nebraska, Office of the Governor, July 6, 2017, viewable at https://governor.nebraska.gov/sites/governor.nebraska. gov/files/doc/press/Red%20Tape%20Review%20Executive%20 Order%202017.pdf.

24. House Bill 1585, Florida Legislature, 2010, http://www. myfloridahouse.gov/Sections/Bills/billsdetail.aspx?BillId=44375.

25. H.R. 10, “Regulations From the Executive in Need of Scrutiny Act of 2011,” The Library of Congress, https://www.congress. gov/bill/112th-congress/house-bill/10; H.R. 367, “Regulations From the Executive in Need of Scrutiny Act of 2013,” The Library of Congress, https://www.congress.gov/bill/113th-congress/ house-bill/367; H.R. 427, “Regulations From the Executive in Need of Scrutiny Act of 2015,” The Library of Congress, https:// www.congress.gov/bill/114th-congress/house-bill/427; H.R.26, “Regulations from the Executive in Need of Scrutiny Act of 2017,” The Library of Congress, https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/house-bill/26.

26. Senate Bill 15, Wisconsin Legislature 2017-2018, https://docs.legis. wisconsin.gov/2017/related/acts/57.

27. House Bill 162, North Carolina General Assembly, 2017-2018 Session, https://www.ncleg.gov/BillLookUp/2017/h162.

28. House Bill 1739, Tennessee General Assembly, 2017- 2018, http://wapp.capitol.tn.gov/apps/Billinfo/default. aspx?BillNumber=HB1739&ga=110.

29. Eric H. Miller and Donald J. Rubottom, “Legislative Rule Ratification: Lessons from the First Four Years,” Florida Bar Journal, Volume 89, No. 2, February 2015, https://www.floridabar.org/news/ tfb-journal/?durl=%2FDIVCOM%2FJN%2Fjnjournal01.nsf%2FA rticles%2F85BA6ABCD1D3571185257DD400580751.

30. Miller and Rubottom, “Legislative Rule Ratification: Lessons.”

31. “Bill Analysis and Fiscal Impact Statement,” SB 1402, The Professional Staff of the Committee on Fiscal Policy, The Florida Senate, February 23, 2016, https://www.flsenate.gov/Session/ Bill/2016/1402/Analyses/2016s1402.fp.PDF.

32. Senate Bill 1402 (2016), The Florida Senate, 2016, https://www. flsenate.gov/Session/Bill/2016/1402/?Tab=Analyses.

33. “House of Representatives Final Bill Analysis: SB 7099,” Florida Legislature, https://www.flsenate.gov/Session/Bill/2018/7099/ Analyses/h7099z1.HHS.PDF.

34. “House of Representatives Final Bill Analysis: SB 7028,” Florida Legislature, https://www.flsenate.gov/Session/Bill/2018/7028/Analyses/s7028z1.HHS.PDF.

35. See, e.g., Christine Sexton, “Florida’s new nursing home generator rules may not be ratified this session,” Orlando Weekly, February 13, 2018, https://www.orlandoweekly.com/Blogs/archives/2018/02/13/floridas-new-nursing-home-generator-rules-may-not-be-ratified-this-session; “Generator rules await legislative action,” News Service of Florida, February 14, 2018, http://floridapolitics.com/archives/256256-generator-rules-await-legislative-action; and “ALF generators issue bumped to budget chairs,” News Service of Florida, March 3, 2018, http://floridapolitics.com/archives/258002-alf-generators-issue-bumped-budget-chairs.

36. “Nursing homes get more time for generators,” News Service of Florida, December 21, 2018, https://floridapolitics.com/archives/284048-nursing-homes-get-more-time-for-generators.

37. “Substantial and Widespread Adverse Social and Economic Impacts of Wisconsin’s Phosphorus Regulations A Preliminary Determination,” Wisconsin Department of Administration, Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, April 29, 2015, https://dnr.wi.gov/topic/surfaceWater/documents/phosphorus/PreliminaryDetermination.pdf. Also see Rep. Adam Neylon and Sen. Devin LeMahieu, “Time to REIN in the Bureaucracy,” Wisconsin State Senator Devin LeMahieu, https://legis.wisconsin.gov/senate/09/LeMahieu/news/columns/3292017 [note: the co-authors were lead authors of the Wisconsin REINS Act].

38. S.L. 2012-135, https://www.ncleg.gov/BillLookUp/2011/H237.

39. S.L.-2015-21, https://www.ncleg.gov/BillLookUp/2015/H158.

40. Theresa Matula and Kristen Harris “House Bill 158: Jim Fulghum Teen Skin Cancer Prevention Act,” Senate Health Care Committee Counsel analysis, May 12, 2015, https://dashboard.ncleg.net/api/Services/BillSummary/2015/H158-SMTU-44(e1).

41. See identical Sections 1.(1)–(2) in SB 1402 (2016) and SB 7028 (2018), Florida Legislature.

42. Miller and Rubottom, “Legislative Rule Ratification: Lessons.”

43. Dawson and Seater, “Federal Regulation and Aggregate Economic Growth.” Studies they cite include Goff (1996), Nicoletti, Scarpetta, and O. Boylaud (2000), Bandiera, Caprio, Honohan, and Schiantarelli (2000), Nicoletti, Bassanini, Ernst, Jean, Santiago, and Swaim (2001), Bassanini and Ernst (2002), Djankov, LaPorta, Lopez-de-Silanes, and Shleifer (2002), Nicoletti and Scarpetta (2003), Alesina, Ardagna, Nicoletti, and Schiantarelli (2003), Kaufman, Kraay, and Mastruzzi (2003), Loayza, Oviedo, and Serven (2004, 2005), and Djankov, McLiesh, and Ramalho (2006).

44. Bentley Coffey, Patrick McLaughlin, and Pietro Peretto, “The Cumulative Cost of Regulations,” Mercatus Working Paper, Mercatus Center, George Mason University, April 2016, https://www.mercatus.org/publication/cumulative-cost-regulations.

45. Dawson and Seater, “Federal Regulation and Aggregate Economic Growth.”

46. Dawson and Seater, “Federal Regulation and Aggregate Economic Growth.”

47. Russell S. Sobel and John A. Dove, “State Regulatory Review: A 50 State Analysis of Effectiveness,” Mercatus Working Paper No. 12-18, Mercatus Center, George Mason University, June 2012, https://www.mercatus.org/publication/state-regulatory-review-50-state-analysis-effectiveness.

48. Jon Sanders, “Periodic review is still working, and it still could do more,” The Locker Room blog, John Locke Foundation, January 9, 2018, https://lockerroom.johnlocke.org/2018/01/09/periodic-review-is-still-working-and-it-still-could-do-more.

49. LB 299, https://nebraskalegislature.gov/bills/view_bill.php?DocumentID=31200.

50. Nebraska Revised Statute 84-907.04, https://nebraskalegislature.gov/laws/statutes.php?statute=84-907.04.

51. Jon Sanders, “Stated objectives and outcome measures: making sure rules work as intended,” The Locker Room blog, John Locke Foundation, February 21, 2017, http://lockerroom.johnlocke.org/2017/02/21/stated-objectives-and-outcome-measures-making-sure-rules-work-as-intended.

52. See Winegarden, “50-State Small Business Regulation Index,” p.9, and cf. “The RFA in a Nutshell: A Condensed Guide to the Regulatory Flexibility Act,” U.S. Small Business Administration, Office of Advocacy, October 2010, https://www.sba.gov/sites/default/files/advocacy/RFA_in_a_Nutshell2010.pdf.

53. “2018 Small Business Profile: Nebraska,” U.S. Small Business Administration, Office of Advocacy, https://www.sba.gov/sites/default/files/advocacy/2018-Small-Business-Profiles-NE.pdf.

54. LB 299.

55. Ricketts, Executive Order No. 17-04, “Regulatory Reform.